Review of Not Just Black and White

In February this year, on another balmy Brisbane evening, I went off to Avid Reader to listen to a panel discussion, ‘Indigenous Women Writing Their Stories’ presented by The Stella Prize and black&write. The courtyard was packed, the stars were out, the wine was cold and the panelists were fantastic.

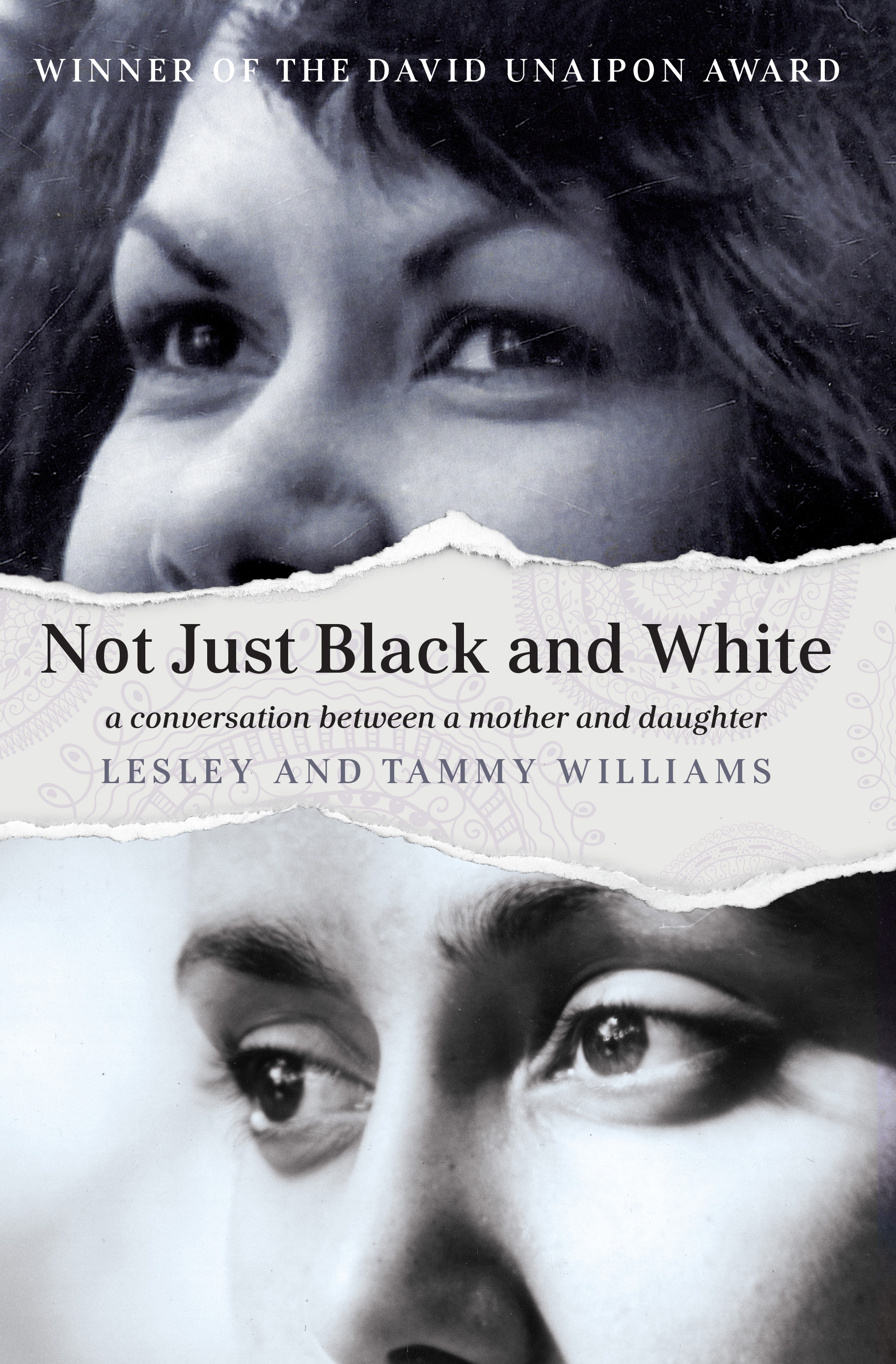

Ellen van Neerven, author of the wonderful Heat and Light, hosted the session, which included Lesley and Tammy Williams, winners of the 2014 David Unaipon award for Not Just Black and White; Melissa Lucashenko, author (most recently) of Mullumbimby; and black&write intern Yasmin Smith. It was a wonderful, stimulating evening. Tammy told a joke about how their book was mistaken for one by the Williams sisters (of tennis fame) in a store (obviously not Avid!).

At the end of the evening, I stepped onto the bus with a copy of Not Just Black and White and started to read. The authors are a mother-daughter duo, and their stories are braided together into a dialogue. The work opens with Lesley’s narrative, which highlights the centrality of place to her identity: ‘The sound of water droplets hitting the geranium leaves brought back childhood memories of rain beating down on the tin roof back home in Cherbourg’ (1). Cherbourg was the Aboriginal settlement in Queensland in which she grew up. The opening passage also provides what was to become one of Lesley’s (and therefore the work’s) driving forces – the search for Aboriginal people’s missing wages and savings that were held in ‘trust’ by the government.

The book is subtitled A conversation between a mother and daughter, and Lesley’s account is in conversation with her daughter Tammy. Lesley began telling her story to Tammy when Tammy was a teenager. She initially spoke into a tape recorder because she would ‘always clam up whenever it came time to put pen to paper’ (3) and thought this was due to her limited education but, as Tammy explains, it was also because Aboriginal culture is an oral culture and Aboriginal people of Lesley's generation were more accustomed to passing stories and memories down through recollection and speech. In the book, Tammy responds to each of her mother’s sections, bringing in her insights as she grows up and becomes a lawyer. Her mother’s personal story, she says, ‘was as entwined in mine as mine was in hers’ (4).

Lesley describes growing up in Cherbourg, the closeness of her family and how they often used humour to survive; her growing awareness of the divisions between races and how this was tied to class; how she went out to work as a domestic servant in the country and in Brisbane and worked hard for no pay, except maybe a ticket to the movies; her evening as a debutante in a lovely dress; her marriage to a man who was initially very good and kind but suffered from depression, which killed him. Lesley then needed to work even harder to support her family, but she was tough and determined. She became an Aboriginal teacher’s aide and she showed Tammy that a girl could be anything she wanted.

Although Tammy also worked hard, she ‘hardly ever saw Indigenous people in the kind of roles I imagined could be for me’ (179). Michael Jackson, however, was one of the first images of a successful black person that she saw. In the Cosby show, she found that the wife of Dr Huxtable was a lawyer. ‘It seemed irrelevant,’ Tammy writes, ‘that the Huxtables were a different kind of black people in a different country. I identified more with this fictitious black family living on the other side of the world that the people I saw regularly on the local streets’ (181). And in this way she had ‘a clear image of at least one professional black woman I wanted to be like’.

Tammy was teased at school, while her mother was continued her fight for stolen wages. Needing to express the continuing injustice she experienced and witnessed, Tammy wrote an essay about racism and the need for role models, which she submitted to a competition run by Michael Jackson’s Heal the World Foundation, and won! She and Lesley travelled to a conference at Neverland and then around America, before attending the World Summit of Children in San Francisco. While travelling, they also learned of similarities between the experiences of Indigenous Australians and ethnic Americans, who were also dispossessed of their land. On their return to Australia, Tammy and Lesley were invited to speak at the United Nations Human Rights Council Headquarters in Geneva, and their community rallied around to help them finance the trip.

In Geneva, Lesley gathered her courage and spoke to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on this trip about Indigenous people’s stolen wages. After this, she figured she could speak to anyone, including the Queensland premier. On her return to Australia, she continued her fight, working with researchers who estimated the amount of the lost wages. She compiled media kits; and organised rallies and community meetings amidst some hostility from white people (Pauline Hanson was enjoying her first flush of power) and from some of the Indigenous community as well. She accessed the government records relating to her family, but the documents she needed most were ‘noticeably missing’ (306). Finally, with the help of an Indigenous woman, Kerrie Tim, the executive director of the Department of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Policy, and her policy advisor, Lesley obtained the passbook showing her savings. It had been held in a safe that had belonged to the former director of Native Affairs. Even despite this evidence, the Queensland government was prepared to fight Lesley in court - the racism that confined Indigenous people in settlements such as Cherbourg was clearly continuing. Eventually, however, the government offered an apology and compensation not just to Lesley, but also to individual claimants.

This was a great book to read. I found Lesley’s account more gripping, perhaps because her recollections were more detailed and descriptive, and her tenacity, intelligence and lateral thinking were incredible. That the passbook was kept locked in a safe also speaks volumes, as does the government's reticence to redress injustice. But Tammy’s account showed how the past moulds the future, and that the qualities parents learn shape their children too. I was glad that this book not only won the David Unaipon award, which meant it could be published, but also the Queensland Premier's award for a Work of State Significance in this year’s Queensland Literary Awards – it means that, although we still have a long way to go, representations of Queensland’s history are finally becoming more inclusive.

This is my fourth review for the Australian Women Writers Challenge.