On Journeys

I’ve made it back from India, where I was battered about with culture shock, but otherwise had an excellent time. My red sony eReader was fantastic, and saved me carrying around the brick-size book five of Game of Thrones, and Edith Wharton’s The Reef which, even for a Wharton fan, was supremely disappointing. I also read Willa Cather’s My Antonia, a recommendation from H., and loved the distilled descriptions of the American countryside. I’ll write up my travels in another post, probably when I get to Parental Unit’s in a few weeks, as I remain waylaid by exhaustion. In the meantime, I have a stack of books on my desk accruing library fines as they await reviewing for the Australian Women Writer’s Challenge, and it seems apt to pick out two which are about journeys.

I picked up Mardi McConnochie’s The Voyagers as she’d been mentioned in James Bradley’s blog, and I loved the cover. It’s the story of Stead and Marina, who meet briefly while Stead, a sailor, has shore leave. After three days, Stead leaves, and not long after Marina sails to London for her musical career, with Stead’s promise that he’ll meet her there at New Year’s Eve. However, Marina’s career is thwarted, the second world war comes, and the lovers spend years trying to find one another.

It took me a while to get into the novel because the writing didn’t grab me, but once I reached the end, I found images lingering afterwards: Marina playing piano at a club in Shanghai, waiting for Stead while Singapore fell, trying to survive in Changi prison camp with an adopted baby. There must have been a wealth of research behind those scenes but it was held lightly; perhaps almost too lightly, I thought, as I craved more detail and depth.

The story didn’t leave me with much to think about, aside from these rather beautiful scenes and one other aspect: Marina’s sister, Bea. An artist living in Paris, she meets Marina in London and takes care of her for a while. When Marina loses her place at the music school after Bea has done all she can for her, Bea’s patience snaps.

‘I have to work,’ Bea insisted. ‘My work is my life. And that means making sacrifices.’

‘You don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Marina said. ‘What have you ever had to sacrifice?’

Bea’s face crumpled a little. ‘I’ve made sacrifices,’ she said.

‘Like what?’ Marina demanded. But Bea just shook her head angrily, refusing to be drawn on the subject. (128)

In the context, the suggestion is that Marina has given up her own child in order to paint.

The internal conflict between an artistic life and motherhood is one that fascinates and concerns me, and I was disappointed that Bea’s story wasn’t returned to, or her dilemma elaborated on. Instead, all we have of her dedication and sacrifice is Stead’s observation of her features: ‘She was older than Marina, with a sterner cast of feature and a very determined jaw. Her eyes were brown, sharp and serious’ (82). However, this was Marina’s journey, rather than her sister’s, so perhaps I was expecting too much in this sense.

The story is also saved from becoming a predictable war-torn romance through its shifting narrative, moving between Stead and Marina’s voices, and backwards and forwards in time, with Stead’s search for Marina becoming a board from which to dive back into the past of Marina’s story. Ultimately, Marina comes across as the more interesting character, her estrangement from music mirroring her loss of self which, in Changi, became a means of expressing a newer, tougher, woman: ‘something inside her began to unravel, and then to knit itself into something new’ (240). Meawhile Stead appears well-meaning, but hopeless, and whose hopelessness, in causing so much heartache, becomes malign.

In all, although it was light, I really quite enjoyed this novel, and am tempted to look up some of McConnachie’s earlier works.

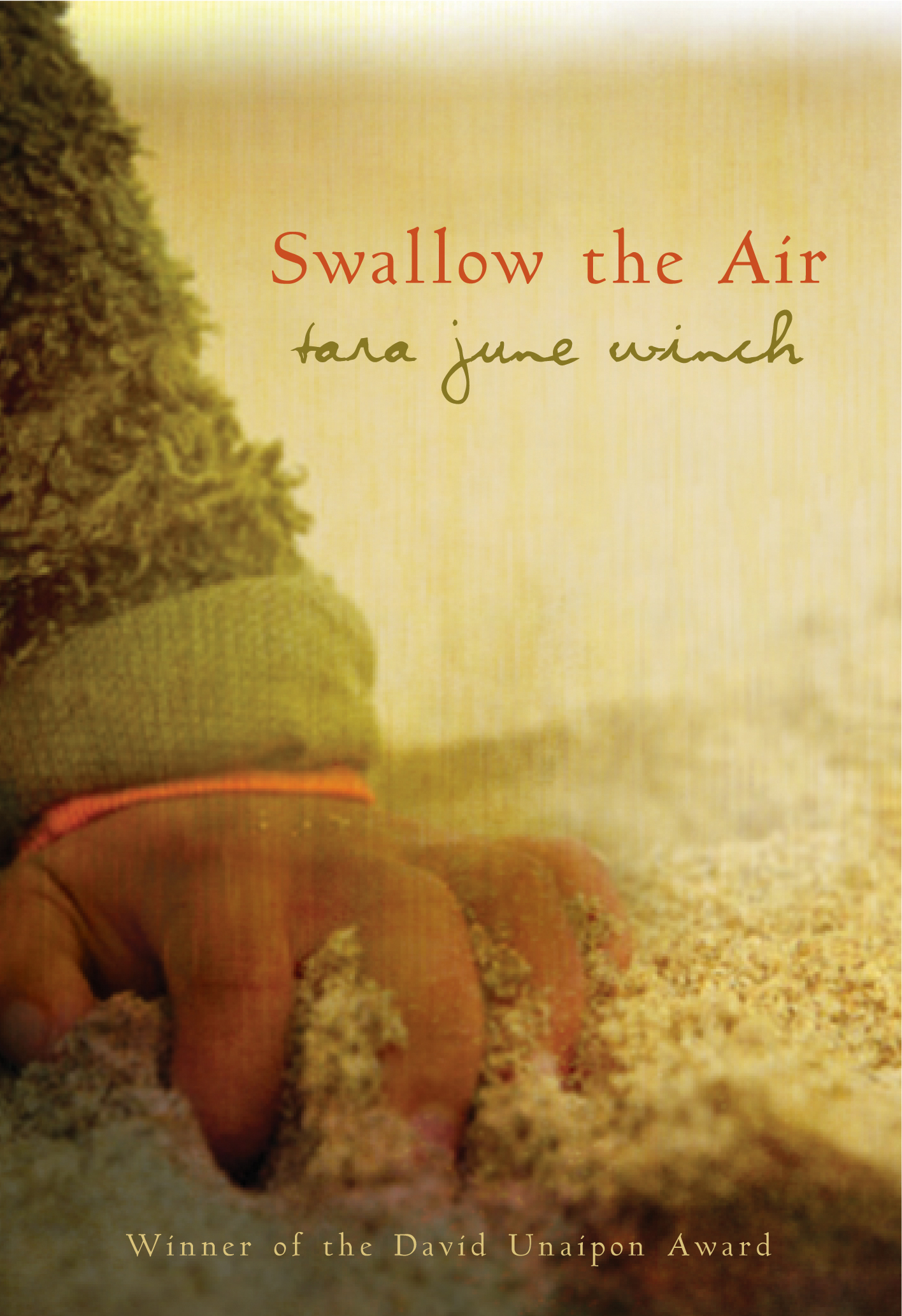

Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air (2006) won the David Unaipon award, the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and was shortlisted for the Age Book of the Year. It’s a series of short stories narrated by May, a young Indigenous girl, as she grows into adulthood. Her father has disappeared, her mother dies, her aunt is an alcoholic, her brother leaves home, and May sets out on her own. Despite abuse, poverty and sadness, the world around her is rendered beautifully through Winch’s poetic writing. Sometimes this is discomforting, such as in ‘My Bleeding Palm’, where a scene of violence is hinted at through the press studs down the side of a man’s tracksuit pants. The popping sound they make reminds May of ‘Bubble wrap. Lemonade burps as Billy and me push each plastic blister between finger and thumb, choking on each other’s laughter. Popping giggles silence violence grunts’ (36). The juxtaposition of lovely memories with the violence of the scene serves to heighten its horror, and far more effectively than if it had been described in detail.

At times the lusciousness of the language becomes a little irritating because the metaphors jump around a bit, as with the first chapter, ‘Swallow the Air’, where a dead stingray is likened to ‘a plastic raincoat sleeping on the stone’, ‘a fat man in a tight suit after a greedy meal’ and ‘an angel fallen’, while its tail is a ‘garden hose’ and its blood oozes ‘paint like liquid, the colour of temple chimes’. There’s just too much going on. At other times, however, the imagery is controlled and works efficiently, such as in the lines ‘We find sherbet-coloured coral clumps, sponge tentacles and sea mats, and bluebottles – we bust them with a stick’ (22). This operates almost at the level of poetry, with the run-on lines and alliteration stopped abruptly by segmenting the sentence with a dash, mirroring the whacking of bluebottles. Winch’s characters are also wonderfully delineated through moving stories, such as her mother scrimping to buy a set of saucepans from a travelling salesman.

This is May’s story about finding herself, her mother’s people, and her home. By the end of her journey she understands that ‘The land is belonging, all of it for all of us. The river is that ocean, these clouds are that lake, these tears are not only my own. They belong to the whales, to Joyce … to Billy, to Aunty, to my nannas, to their nannas, to their great nannas’ neighbours. They belong to the spirits’ (183). It’s a testament to the will of Indigenous people that they struggle to rebuild their families fractured by white settlement, and they try to recover that wholeness described by May, and that they continue do so after centuries of ill-treatment, as an old Indigenous man says to May when describing the abuse perpetrated by Catholic priests on ‘the little fellas … Who’s gunna speak up for em little fellas? Other people don’t understand, when that bad spirit happens to family, it stays in the family, when we born we got all out past people’s pain too. It doesn’t just go away like they think it does’ (170).

Both May and Marina show their readers that, by journeying through difficult terrains, and by persisting despite heartache, one can reach a stronger sense of self. Incidentally, both books are a great read if you’re ever on the road, or in the air.